Daedalus Ignored: The Risks of Developing Psychic Abilities

Words of Wisdom from Alois Wiesinger

This article is a continuation of my presentation and analysis of Alois Wiesinger’s book, Occult Phenomena in the Light of Theology. Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

Wiesinger says that the preternatural gifts of the soul (i.e., “psychic gifts”) can be won back through “true mysticism,” but he is wary of other contexts in which they may be developed:

The harm done in the aggregate to mental health by spiritualism and occultism is so great that it justifies the avoidance of certain practices which are innocent enough in themselves, but which tend to lead to an unhealthy mysticism. (p. 195)

His example in this context is dowsing—a practice of divining the location of underground resources like water, oil, or minerals. Though it may be morally neutral, Wiesinger is concerned that activation of the soul’s latent powers may carry risks.1 Those who purposefully induce trance states in order to activate the powers of the subconscious—outside of any kind of spiritual protection—may end up in a state of “complete madness.” He mentions the example of one famous trance medium, Hélène Smith, who indeed “died in a madhouse” (pp. 127–128).

Furthermore, outside of a healthy “true mysticism,” practitioners may develop an egomania and come to an unhealthy reliance on their psychic prowess. The aforementioned trance medium—though she demonstrated some noteworthy psychic abilities—was also proved to be delusional in some of her grandiose performances:

she believed herself to be in communication with an inhabitant of Mars and also spoke the Martian language, which turned out to be a debased form of French. All we heard from the said Martian was a selection of what was at the time already being written concerning the putative inhabitants of that planet. Thus it was in every case the subconscious and nothing else that came to the surface in her somnambulistic states. (p. 127)

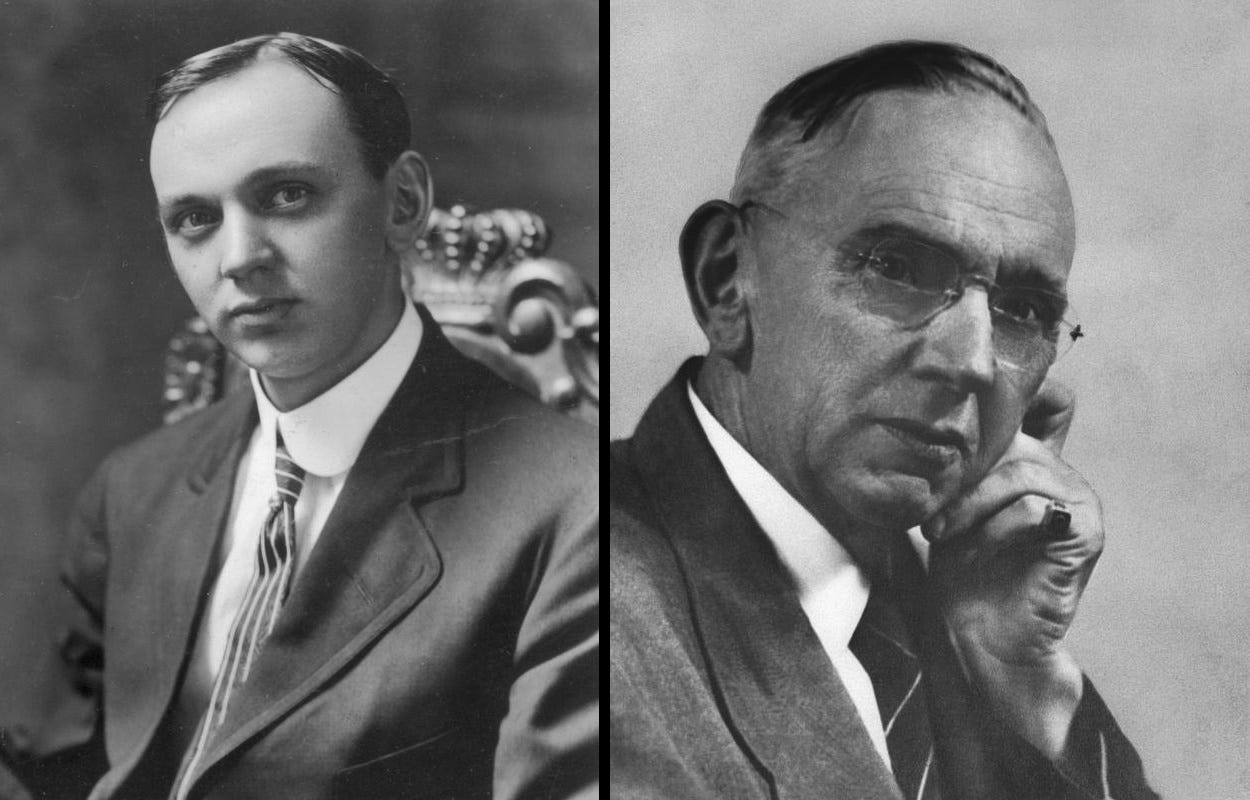

In our first essay, mention was made of Edgar Cayce’s remarkable ability to enter a trance state to diagnose and treat illnesses with startling success. Yet, it should be remembered that Cayce also pronounced on a number of esoteric subjects in his trance states: on unprovable metaphysical conceptions like reincarnation and on demonstrably wrong ideas like the location of Atlantis. Indeed, Cayce is a sad example of a committed Christian abandoning the moorings of his faith and placing too much trust in his own psychic abilities (in large part through the flattery and direction of theosophist Arthur Lammers).

To return to the advice of the Anglican Deliverance handbook:

Natural, psychic intuitions are not necessarily bad, though they may be flawed (as any natural human propensity may be flawed by the effects of the Fall). The danger comes when people trust in them without subjecting them to critical scrutiny, and assume that because they are psychic they are beyond the need for questioning.2

And though one cannot posit the influence of a demon in every instance, neither can we rule it out. Parapsychologists are reluctant to admit the interaction of non-human, evil spirits, but Christians who accept their existence should not rule out their involvement whenever the spirit realm is engaged. From the letters of St. Paul to the visions of St. Anthony, Christians have long understood that we live in an embattled cosmos. This caution is especially warranted in the case of those who consciously seek to interact with a “control” or “spirit guide.”

A person who lays herself open to any stray psychic influences . . . may not always find herself becoming the mouthpiece of entirely good forces. Christians should be wary of any person who claims to be ‘controlled’ by any spirit other than the Holy Spirit of God, and they should constantly test the spirits to see whether they are wholesome or baneful.3

Wiesinger himself expresses extreme caution in developing these abilities—even for those in a Christian context:

Though it is certainly our duty to co-operate with the graces of God, it would nevertheless be rash to overlook the dangers involved in cutting out our normal sense life while we are still on earth, dangers that can only be eliminated in the mystical life that is truly led by God and guided by his grace, but which are ever-present in the baser forms of mysticism. (p. 285)

Wiesinger suspects that many Christians are not mature or disciplined enough to safely pursue this recovery of the soul’s power. They may even be sucked in to a false form of mysticism:

it is all too rare for men to undertake the labour of mounting the first steps in the mystical life; their love and readiness for sacrifice are too weak for that.

For that very reason, however, they are all too ready to join the heathen in treading the paths of the occult and indulging themselves in pseudomysticism, and to dissipate their energies in magic, spiritualism and theosophy, to their own physical and spiritual ruin. (pp. 285–286)

Though Pentecostalism had existed for a few decades when this book was written, the movement was rather isolated and marginalized. The subsequent outbreak of the broader Charismatic renewal did not come about until after Wiesinger’s death. One wonders what he would have thought about this contemporary effort to restore the spiritual gifts to the common man. Would he have approved? Or would he have warned against an excessive eagerness to unlock the soul’s power?

While I consider myself a part of this movement, one cannot deny that it often attracts “miracle chasers” or wannabe prophets. The pejorative “Charismatic voodoo,” though harsh, sometimes captures the practices of those who want to conjure up spiritual power outside of the context of spiritual maturity. Just as Daedalus fashioned wings for Icarus but warned him not to fly too close to the sun, Wiesinger opens the door to the legitimate usage of these abilities but warns against “pseudomysticism.” Those who ignore him are doomed to the same fate as the overconfident Icarus.

Natural Mysticism

Wiesinger spends some time speaking to the “natural” mysticism that has been witnessed across all times and cultures. How do we make sense of those who “loosen” the soul and exhibit dramatic feats of power outside of Christendom?

In the first place, he affirms the true spiritual nature of these experiences, writing that “We have no reason for doubting Plotinus” and his descriptions of mystical out-of-body experiences (p. 42). He further notes that the Buddha “had earlier achieved something very similar by means of continuous contemplation” (p. 258), and he notes that this

ascetic mysticism is the essence not only of Buddhism, but of the whole of Hinduism; for the latter is a religion of dreams and suprasensory experiences. Today the Yoga cult teaches a kind of forced contemplation achieved by means of mortification, breathing exercises, rhythm and fasting, the object being to attain union with the absolute. . . .

Through such practices and training the fakirs reach a stage where they are able to discontinue breathing and can allow themselves to be buried alive for half an hour, or even for six hours, or for weeks or even months; they can lengthen the rate of their pulse, can walk on fire without being burnt. (p. 258)

Turning to more contemporary times, he further points to the Theosophy of Blavatsky and the Anthroposophy of Steiner, both of which “bear witness to an innate longing on the part of all peoples for some direct connection with the purely spiritual” (p. 260).

All of these systems seek some sort of apotheosis of the soul’s powers, a glorious entrance to the realm of eternity. Yet, outside of Christ, “man never gets further than the gateway” (p. 270). In his posthumously published Letters to Malcolm, C.S. Lewis spoke to this notion:

Mystics (it is said) starting from the most diverse religious premises all find the same things. These things have singularly little to do with the professed doctrines of any particular religion—Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Neo-Platonism, etc. . . . The agreement of the explorers proves that they are all in touch with something objective. It is therefore the one true religion. And what we call the “religions” are either mere delusions or, at best, so many porches through which an entrance into transcendent reality can be effected4

Yet Lewis remains “doubtful about the premises” of this popular theory:

Did Plotinus and Lady Julian and St. John of the Cross really find “the same things”? But even admitting some similarity. One thing common to all mysticisms is the temporary shattering of our ordinary spatial and temporal consciousness and of our discursive intellect. The value of this negative experience must depend on the nature of that positive, whatever it is, for which it makes room. But should we not expect that the negative would always feel the same? If wine-glasses were conscious, I suppose that being emptied would be the same experience for each, even if some were to remain empty and some to be filled with wine and some broken. All who leave the land and put to sea will “find the same things”—the land sinking below the horizon, the gulls dropping behind, the salty breeze. Tourists, merchants, sailors, pirates, missionaries—it’s all one. But this identical experience vouches for nothing about the utility or lawfulness or final event of their voyages.

Thus Lewis, like Wiesinger, affirms the essentially spiritual nature of these spiritual transports across all cultures, for they are all engaging in a similar “temporary shattering” of the bodily senses in order to focus on the soul’s ascent. A similar “departure,” however, does not guarantee a similar “destination”:

I do not at all regard mystical experience as an illusion. I think it shows that there is a way to go, before death, out of what may be called “this world”—out of the stage set. Out of this; but into what? That’s like asking an Englishman, “Where does the sea lead to?” He will reply “To everywhere on earth, including Davy Jones’s locker, except England.”

More:

The lawfulness, safety, and utility of the mystical voyage depends not at all on its being mystical—that is, on its being a departure—but on the motives, skill, and constancy of the voyager, and on the grace of God. The true religion gives value to its own mysticism; mysticism does not validate the religion in which it happens to occur.

As Lewis concludes: “Departures are all alike; it is the landfall that crowns the voyage.” This is congruent with Ben Witherington’s remarks on biblical prophecy: “ecstasy certainly cannot by itself help to distinguish true from false prophecy.”5 The lesson here, which I find helpful, is that the bare spirituality of an experience does not automatically prove it to be good or evil. One must consider the source.

Remote Viewing: Licit or Verboten?

At this juncture, I’d like to apply some of Wiesinger’s insights into the phenomenon of remote viewing—particularly those programs contracted by the US Government to employ psychically gifted men and women who could, from the confines of a laboratory, remotely spy on the Soviets, locate hostages, and foil smugglers. For reasons of security, the program changed names every five years or so, and it eventually became known as “Star Gate” to the wider public, the operating name of the early 90’s. The whole scenario raises questions for Christians, who might be inclined to consider remote viewing a form of divination which is so vehemently excoriated in the Old Testament (Deut. 18:9–14; 2 Kings 17:17–18; 21:6).

Not only must we ponder whether Christians can engage in this practice themselves, but we must also ask whether conscientious government employees can employ these psychic remote viewers in good faith—would this be considered “consulting diviners” and morally unacceptable? This question is not new. Annie Jacobsen reports that, at one point during the program’s tenure, “A fundamentalist Christian group aligned with a powerful congressman declared remote viewing to be the Devil’s work and lobbied to have the program canceled.”6

In the future, I intend to write a more focused article on what the Bible says about “sanctioned” versus “unsanctioned” divination, but, for the present, it should be acknowledged that many of these prohibitions on divination, in their original contexts, were intricately linked with the worship of false gods. Not all forms of divination were prohibited. In fact, some forms of divination were approved and commanded by God.7

Star Gate (and its predecessors) included a religiously diverse cast of remote viewers. The “original” remote viewer himself, Ingo Swann, was a Scientologist. Another early viewer, Pat Price, was raised in the LDS Church (Mormon), yet had become a Scientologist by the time of his involvement with the program. Tom McNear, on the other hand, was (and is) a committed Evangelical Christian, and was considered by Swann to be his best student:

By the end of his training, which included all seven stages, Tom McNear had become so good at identifying training targets that Ingo Swann confided in colleagues, “he is better than me.”8

Other notable viewers in the program included Paul Smith, a Mormon, and Bill Ray, a Roman Catholic.

In the remote viewing sessions, the viewers would “cooldown” to clear their minds, remove sensory distractions, and (hopefully) enter a state of flow conducive to receiving the “signal.” Smith did this through music, but Bill Ray did this through praying the Ave Maria, and Tom McNear did this through his own personalized prayer.

Regarding their own religious perspectives, Ray—who remains a practicing Catholic who attends mass and fasts during Lent—believes remote viewing to be a natural ability with “a spiritual quality to it.” McNear has said something similar:

People often ask me, “Where do these abilities come from?” I believe these are all our God-given perceptions. The Bible says: All things created, in heaven and on earth, both seen and unseen, are created by God. God created all of us. If one of us can do it, all of us can do it.

For both of these Christians, remote viewing was a way to serve their country using their God-given talents. They were, it would seem, patriotic psychics! There was no question of this being an occult or demonic practice. Rather, in Wiesinger’s terminology, they were utilizing their latent soul power in the service of national security.

Yet this perspective of it being a purely natural human ability was not shared by all of the viewers in the program. In 1986, Angela Ford (whose name at the time was Angela Dellafiora) was recruited into the psychic spying program. Unlike the other viewers, she embraced the more occult dimensions to her “gifting.” This caused quite the stir among the other viewers:

Paul Smith says what incensed him most was that Dellafiora called herself a psychic, which made him and every other soldier wince. “At Fort Meade we’d worked hard to establish ourselves as remote viewers,” says Smith, “to separate the process from the terrible stigma of the occult.” Dellafiora’s insistence she was psychic flew in the face of all that, he says. “She read tarot cards and did automatic writing,” he says, and “this was unacceptable” to a unit of military men and women.9

Beyond these suspect practices, Ford also channeled a handful of “spirit guides” who would provide her with preternatural knowledge. Paul Smith expressed his uneasiness not simply with the occult nature of channeling, but also with the inherent problems with trusting such spirit guides: “If you can’t vet them you can’t trust them.”10 Furthermore, it would be virtually impossible to ascertain the motivations of such discarnate entities.

Some would explain away the objective existence of these “spirit guides” as a mere focusing point for Ford’s psychic powers. Wiesinger himself favors this approach when treating the topic of mediumship in general (pp. 217–221).11 Yet we should not be so quick to dismiss Ford’s own conviction that she received information from outside spirits. As previously mentioned, Augustine thought that divination might be performed “sometimes through the interaction of another spirit.”

Perhaps the spirits who assisted Ford in her (admittedly powerful) psychic abilities were not entirely benign. In her recent interview with Shawn Ryan (a relatively new Christian himself), many viewers noticed her visible discomfort, darting eyes, and stiff demeanor immediately upon Ryan’s mention of the crucifixion (indeed, this is the second-most replayed section of a nearly 3-hour interview). After this unusual display from Ford, Ryan breaks up the disquieting silence and simply asks, “Do you not want to talk about that?” and moves on.

Those who have read the “Diagnosing the Demonic” section of A Magical World will recognize this as a classic symptom known as “aversion to the sacred.”12 Experienced exorcists point to such reactions against Christ as one form of evidence for demonic involvement. Watchman Nee certainly overstated his case when he wrote that “all who develop their soul power cannot avoid being contacted and used by [an] evil spirit.”13 But it seems that, at least in Ford’s case, he may have been right.

Proceed with Caution

Overall, my impression is that there may be both legitimate and illegitimate ways of engaging in remote viewing (and similar practices). While I would love to hear some clarifying comments from Tom McNear, I consider his involvement in psychic spying, as a Christian, to be perfectly legitimate.

On the other hand, it seems to me that Angela Ford was likely a channel for the “stray psychic influences” mentioned earlier. Someone in her position may need Christian deliverance and should not be contracted by believers in government programs like Star Gate. In my opinion, the end (actionable psychic information) would not justify the means (involving the unit with unvetted spirits).

Christians who might be in a position similar to McNear should ensure that they are spiritually mature enough to engage with the latent powers of their soul. They should regularly offer prayers of protection, committing to heart Scriptures like Psalm 46, Psalm 91, and Ephesians 6:10–18. Ultimately, they must commit their gifting to the Lord and trust in His protection in the matter.

Others, however, may be unable to engage in such programs due to spiritual immaturity. The Anglican Deliverance handbook affirms that

psychic gifts, like God’s other gifts, should only be cultivated in relationship to God’s will, and their exercise should be seen as a call to deeper commitment to God and a closer walk with him. If a person with such gifts finds that he cannot do this, and that he is getting things so out of proportion as to be unbalanced, then he should realize that the danger signals are sounding and he should withdraw at once and totally. Just as a person who cannot control his alcohol intake has to eschew something which most people can use happily and in a responsible way, so some people cannot retain their balance in respect of psychic forces and have to forgo the use of them.14

We must understand that those who deal with the innate powers of the soul—including Christians—are dealing with something very powerful. This does not mean that these powers are inherently evil, only that they must be treated with trepidation. The rule among the greatest alpinists, “respect the mountain,” has relevance here. As does Alexander Pope’s famous line: “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” To offer another analogy, nuclear fission can bring about both tremendous good as well as tremendous evil; the outcome depends on how the technology is handled.

This is perhaps why my erstwhile professor Jimmy Akin has exhibited a hint of ambivalence on the potentiality of his own psychic abilities. Akin, a Roman Catholic, has engaged in some minor psychic experiments, such as spoon bending and even being an “outbounder” for a remote viewing experiment.

On the other hand, when my colleague Ben Bedecki asked why he hasn’t attempted to induce an out-of-body experience (OBE), Akin replied that “two issues have deterred me.”15 The major issue is simply that developing this skill can take a tremendous amount of time—a precious commodity to him. The other issue that he mentioned, however, is worth considering. Before engaging in such a practice, he “would like a little greater certainty of whether something’s leaving the body or not” (referring to the longstanding debate as to whether these experiences are a real exit from the body or simply a projection of ESP). He continued: “I would feel more comfortable with doing traveling clairvoyance than actually sending something out.”

It must be said that he was rather open to the idea, even saying “maybe someday when my schedule lightens up” he might attempt it. Yet his comment about the potential vulnerabilities of being separated from the body are well advised. Other Christians should remember that psychic abilities and associated trance states carry risks. We should be neither paranoid nor naive about these risks, which is precisely the direction advocated by Wiesinger. He is wary about many usages of psychic abilities, but is positive toward others, including medical diagnoses (p. 241), healing (p. 199), legal detective work (p. 159), and artistry (p. 264).

Use the wings, but don’t fly too close to the sun.

Concluding Thoughts

Wiesinger’s framework for understanding psychic abilities as a latent function of the human soul offers, as previously said, tremendous explanatory power. It provides us a way out of the “demon of the gaps” paranoia when dealing with this universal human experience. On the flip side, the notion of the “loosening” of the soul tells us that we should yet be careful anytime that these powers are engaged.

“Perilous to us all are the devices of an art deeper than we possess ourselves.”

— Gandalf the White

The author of the Book of Wisdom was right to observe that “a perishable body weighs down the soul, and this earthy tent burdens the thoughtful mind” (9:15). God, in his own wisdom, seems to have dulled the activity of these abilities, and it is only through “true mysticism” and spiritual maturity that they should be re-awakened. Some will manifest “certain roots of the paradisal gifts” during their lifetime, while others will experience the full effect after death, when the soul separates from the physical body (p. 95). This was John Flavel’s understanding of telepathy,16 and it is also reported in Near-Death Experiences.17

Wiesinger’s hypothesis does have its weaknesses. Some psychic feats seem to be achieved with little to no (visible) state of trance. Both Tom McNear and Bill Ray have affirmed that Controlled Remote Viewing (CRV) is not performed in a trance or altered state of consciousness (ASC), only in a state of a cleared mind. It is to be contrasted with Extended Remote Viewing (ERV), in which an ASC is deliberately induced. Wiesinger might have retorted that in such gifted seers, the “loosening” of the soul is so subtle that they do not even recognize the elements of trance. Whatever the case, more work would need to be done in order to validate Wiesinger’s work.

Overall, though, I think Christians should deeply engage with this work of tremendous erudition, thoughtfulness, and imagination. Abbot Wiesinger has done the legwork of integrating theology with parapsychology, and I believe that, despite some minor flaws, he has succeeded.

I have previously commented on dowsing in an interview with Nikola K. I agree with Wiesinger about it being morally neutral in and of itself.

Michael Perry, ed., Deliverance: Psychic Disturbances and Occult Involvement, SPCK Classics, 2nd edition (London: SPCK, 1996), 51.

Perry, Deliverance, 56.

This and the following quotations come from C.S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, unpaginated digital edition.

Ben Witherington, III, Jesus the Seer: The Progress of Prophecy (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2014), Kindle Location 397.

Annie Jacobsen, Phenomena: The Secret History of the U.S. Government’s Investigations into Extrasensory Perception and Psychokinesis (New York: Back Bay Books, 2017), 273.

See my discussion of this topic in A Magical World: How the Bible Makes Sense of the Supernatural (Independent, 2024), starting on page 103, as well as in my lengthy footnote #43, which can be found on pages 113–114.

Jacobsen, Phenomena, 314.

Jacobsen, Phenomena, 316.

Similarly, in the context of Ouija board usage, the Anglican Deliverance handbook notes that “we have no means of telling whether the messages given to us by the board are the work of well-meaning and truthful spirits, or ones which are evil and intent on deceit” (p. 58).

It should be acknowledged, however, that part of Wiesinger’s goal was to disprove “the spiritualist hypothesis”—the claim that the souls of the departed can be summoned at will.

McGuire, A Magical World, 156–163.

Watchman Nee, The Latent Power of the Soul (New York: Christian Fellowship, 1972), 29.

Perry, Deliverance, 55–56. The handbook continues: “But this is rare; most people, with the wise counsel of a spiritual director, can learn to cope with the gifts God gives them—even psychic gifts.”

From a Q&A session after Jimmy’s weekly lecture for “Introduction to Parapsychology” at the Rhine Education Center, 13 November 2024.

McGuire, A Magical World, 109: “[Flavel] speaks to these anomalous instances of spirit-to-spirit communication as a foretaste of the heavenly state, when there will be ‘an ability in those blessed spirits silently, and without sound, to instil and insinuate their minds, and thoughts to each other, by a meer act of their wills,’ just as we now can communicate our thoughts to God without the use of our physical senses.”

McGuire, A Magical World, 213: “The soul hypothesis is further strengthened when we take into consideration the many reports of telepathic communication and clairvoyance common to NDEs. It is the norm for NDErs to communicate wordlessly, mind-to-mind, with the otherworldly beings in their encounters, and they are likewise able to see objects at great distances with ease. In this state of being, the soul seems to enjoy an unleashing of the type of ESP abilities discussed in chapter 4. If, then, our conclusions about these abilities being intrinsic to the human soul have any merit, it would naturally follow that the disembodied soul of an NDEr will experience these abilities in greater measure, which is precisely what we find in the case reports.” Wiesinger (p. 89) calls this form of telepathy “a direct noopneustic connection of souls without any mediation of the senses, a connection of a kind that only subsists between pure spirits and one which came to an end after sin.”

I am by nature very skeptical but I have had some experiences that give me pause. Perhaps someday I will share them with you. For now, thank you for a substantive series of articles on a very intriguing topic. I look forward to your upcoming article on “”sanctioned” versus “unsanctioned” divination.””