Can the Soul be “Loosened” from the Body?

An Analysis of the Wiesinger Hypothesis for Paranormal Abilities

“Theology teaches us that in Paradise man possessed powers which were afterwards lost to him. The question is, which powers were lost completely, which were merely weakened, and whether certain of these powers, which may have remained latent, might not in certain circumstances be capable of revival.” — Alois Wiesinger

This Fall I participated in two parapsychology courses from the Rhine Education Center taught by the legendary Jimmy Akin. The textbook for one of our courses—the fifth edition of Irwin and Watt’s Introduction to Parapsychology—noted the common criticism that that the field of parapsychology is “just a collection of facts without any theory.”1 While this sentiment is of course an overstatement, it is certainly the case that we lack a consensus theory of how psychic functioning works.2 While researchers have accumulated substantial evidence for ostensible telepathic, precognitive, and mind-over-matter abilities, they have not, as yet, come to agreement on the mechanism underlying these phenomena.

The aforementioned textbook does survey some of the proposed theories for “psi” (a catch-all term for psychic functioning). Some posit a form of electromagnetic waves (Michael Persinger), while others have attempted to relate these mysterious abilities to quantum mechanics (Evan Harris Walker).3 Researchers are, however, disinclined to consider “mystical” interpretations of these phenomena,4 in an effort to safeguard their field of research from the baggage of religious frameworks and to avoid models “inaccessible to empirical scrutiny.”5

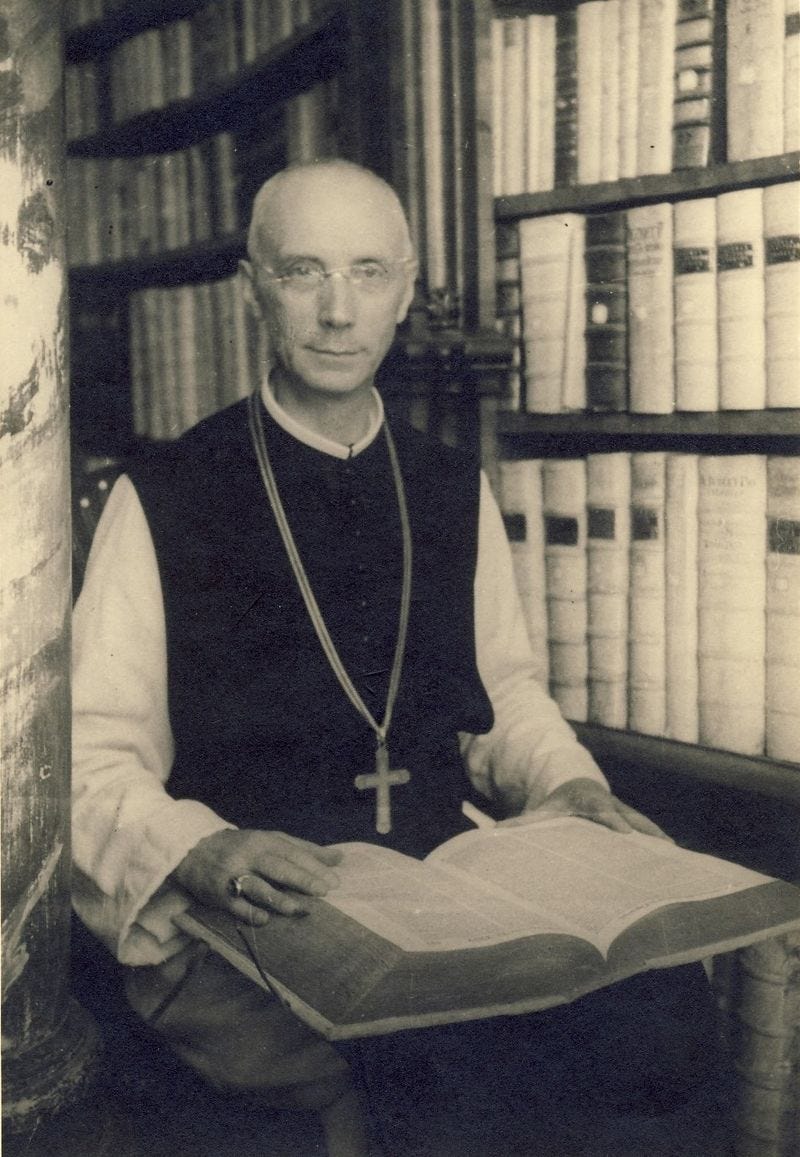

This is where the subject of this article comes in—a book recommended by Akin and entitled Occult Phenomena in the Light of Theology, written by Alois Wiesinger, a Cistercian abbot educated both in the scholastic tradition as well as in the budding field of parapsychology of his day. The first German edition was published in 1948, and the English edition from which I quote was published in 1957. Despite its age, however, it holds up remarkably well almost 70 years later. (Note that he uses the term “occult” in the classical sense of hidden or unknown phenomena, without the automatic “evil” or “demonic” connotations the term has today.)

Because of his cross-disciplinary education in both parapsychology and theology, Wiesinger avoids the Scylla of skepticism and the Charybdis of attributing the unknown to devils—an approach he aptly calls “demonomania” (p. viii).6

Instead, he opts for a synthesis between the findings of parapsychological research and the classical Christian conception of the human soul (which has a distinctly spiritual element), the latter being the source of what we today call psychic, occult, or preternatural abilities.

Furthermore, he supplements his hypothesis by arguing that psychic abilities are a latent, residual artifact of the abilities that man possessed prior to the Fall, as expressed in the introductory quote. This explains why these abilities are manifested only rarely and tend to have weak effects when they do so. Abilities of second sight, dowsing, telepathy, energy healing, remote viewing, xenoglossy, precognitive dreams and visions are all widely attested in human experience, and all of them seem to be, for the most part, sporadic and unreliable. Even in some of the most “gifted” subjects the “hit rate” is far from perfect. Consider, for instance, that the “black belt” of remote viewing himself, Joe McMoneagle, only succeeded 44% of the time, according to Edwin May, who oversaw “thousands” of his remote viewing sessions. And Hubert Pearce’s legendary success in divining Zener cards never amounted to much more than a 30% hit rate.

Wiesinger theorizes that the spiritual aspect of the soul is, in its normal state, bound to the body and does not exercise its purely spiritual functions.

(a) Normal state of the soul. The soul penetrates and informs the body down to the last cell, down to the last atom . . . and normally does not extend beyond the body in its activities. Here the principle applies that nothing is in the understanding that was not first in the senses (p. 58)

However, in an abnormal state, this “spirit-soul” can be fully or partially “loosened” from the body and exercise these functions.

(b) Abnormal state of the soul. The soul is in its lower part (the corporal soul) “body-bound” and in this lower part contains the anima vegetativa, sensitiva and intellectualis, that is to say the living animal, vegetable and intellectual principle, but it rises above these with that part that is designated as the anima spiritualis or “spirit-soul” and which can be contrasted with the lower or “corporal” part of the soul. . . .

The spirit-soul can in certain circumstances partially withdraw itself and its body-bound part from the life of the senses and allow its activity to reach out beyond the body. From this there result phenomena such as we encounter in occultism and to some extent in the mystic life. (p. 58)

Though he writes as a Catholic, his approach allows for common ground with all Christians, with one “Evangelical pastor” writing in response to the book: “To me as a Protestant the fundamental idea is both noteworthy and surprising, that not all the faculties of the soul were lost in the Fall, but that a ‘Paradisal residue’ remains” (p. 48).

And though (as can be seen from the above quotations) he ultimately aligns with Aristotle’s holistic model of the soul against Plato’s hard dualism, Wiesinger still has a soft spot for Platonism:

Aristotle seems to make the unity of the soul much clearer than Plato, who seems to overemphasize the element of spirituality and thus to dissolve this unity. Plato, however, is a better teacher of that other truth which today tends to be so widely forgotten, namely that the soul does possess an element which is pure spirit and nothing else. (p. 11)

While I am not qualified to pronounce a judgment on the scholastic conception of the soul, I can say that Wiesinger’s overall hypothesis has merit whether or not one adopts Aristotelian-Thomistic categories. Those who don’t buy into the entire medieval synthesis can still appreciate the basic thesis, namely, that psychic abilities are faculties of the human soul which have been diminished (but not wholly extinguished) by the Fall, and which can be manifested upon the soul’s separation from the body.

Wiesinger’s hypothesis, to be clear, builds on previous philosophers (as it should). He cites both Plato and Aristotle in support of his “loosening” model before quoting at length the Stoic Posidonius of Apameia (135–51 BC):

There is, however, yet another method of prophecy that proceeds from nature; this proves how great is the power of the spirit, when it has been released from the sensual organs of the body. This occurs especially in sleep and in ecstasy. . . . the souls of men, when they are sunk in sleep and loosed from the body or when rapt in ecstasy and wholly free from their appetites, are thrown back upon themselves, behold things which, while bound to the body, the soul cannot see. But when the soul is in sleep released from its connection and contact with the body, it remembers the past, sees the present and can contemplate the future. (p. 40)

He goes on to cite related frameworks of the human soul from a number of writers from antiquity, including Philo and the Plotinus, summarizing this ancient view as follows:

When the body had withdrawn itself, the soul could function as a pure spirit, could contemplate God, and apprehend truths to which others were blind, could prophecy [sic], experience second sight and act upon material things, as is the nature of pure spirits. This corresponds with the views of all Neoplatonists such as Philo, Porphyrius, Iamblichus, Proclus. All these ascribed second sight, true dreams, and apparitions to the special powers of the human soul. Indeed this is the consistent teaching of antiquity, and it was from this starting point that Christian writers such as Tertullian, Augustine and Gregory the Great proceeded, though in the time that followed the doctrine was more and more allowed to lapse into oblivion; a confused belief in demons and magic took its place.

Indeed, he later includes a citation from Augustine, who describes ecstasy as follows:

When the soul’s attention has been completely diverted from the senses of the body and utterly torn away from them, there follows that state which one calls ecstasy. Then a man sees nothing, whatever bodily objects may be present, even though his eyes are open, nor are any voices heard. . . . [Ecstasy is] a condition in which the soul is more withdrawn from the bodily senses than it is in sleep, but to a lesser degree than in death. (p. 277; from Augustine’s Literal Commentary on Genesis 12.12)

States of Trance: A Partial “Loosening” of the Soul

Though the term “altered states of consciousness” (ASCs) was not in common use prior to the work of Charles Tart,7 the underlying concept informs Wiesinger’s approach to the “loosening” hypothesis. He argues that trance states may be the key to understanding manifestations of paranormal abilities. After arguing that the psychic powers of the “subconscious” (as understood by parapsychology) and the spiritual powers of the “soul” (as understood by faith) should be seen as one and the same, he writes:

there are the pieces of knowledge which man is able to acquire when in an abnormal state, and which come from sources that are not accessible to the soul in its body-bound state; these are, however, open to the soul when it has been freed from the body, and lie stored up in the subconscious, and it is only in the state of trance that, as through a slit, they become apparent. (p. 68)

These altered mental states may come about through various means: hypnosis, soporific music, meditation, fasting, crystal gazing, ingesting drugs, breathing incense, prolonged prayer, or other means of asceticism. These practices, in one form or another, overlap between pagan shamans, Indian fakirs, Buddhist monks, and even Christian mystics.

For each of these “gifted” peoples, there is a common theme of trance states (and a withdrawal of the ordinary senses) being associated with psychic functioning.

A special form of these pathological dreams is to be found in the waking dreams which intermittently occur in the so-called second sight of the Spökenkieker in Westphalia and among similarly endowed persons in Scotland, the Tyrol, and other places where the inhabitants live far away from the noise and bustle of ordinary life and consequently lead a relatively monotonous life conducive to day-dreaming. In such people there is a natural tendency for sense perceptions to be dulled—as it is with the Indians or the Taoists of the Gobi deserts and the Druids or magicians in the woods. (p. 115)

Wiesinger’s hypothesis states that the paranormal feats of magicians, prophets, psychics, and mystics can be attributed to the human soul’s innate powers, once the spiritual component has been released from its bodily counterpart. Trance states are, he says, one way in which that “spirit-soul” can be partially separated from the body.

These states can be either spontaneous or self-induced: “trance is a form of self-hypnotism, and is regularly practised by those persons who produce occult phenomena” (p. 136). Thus practitioners are known to use one of the aforementioned methods to prepare themselves to receive clairvoyant knowledge, healing power, or preternatural “vision” into the spirit world. Wiesinger correctly notes that a trance state falls on a spectrum rather than being a simple binary: “such a state actually obtains in greater or lesser degree.” This is why in some practitioners “appearances would seem to indicate that there was no trance at all” (p. 136)—they may simply be involved in a “low-level” trance.

This framework comports with what we know from the field of remote viewing, in which one modality specifically aims for a trance state in order to maximize the effectiveness of the psychic “signal” over against the “noise” generated by the normal waking consciousness.

Veteran remote viewer Paul Smith explains:

In Extended Remote Viewing, or ERV for short, a viewer relaxes on a bed or other comfortable support and tries to reach a “hypnagogic” state–a condition at the borderline between asleep and awake. . . . The room is darkened and soundproofed if possible.

As the viewer reaches the edge of consciousness, a second person in the room, the monitor (also known as the “interviewer”), begins the session by quietly giving directions to the viewer to access the desired target.

He goes on to explain the reasoning behind this modality:

Remote viewing is based on the theory that remote viewing impressions bubble up from the subconscious. When trying to move subconscious impressions into waking consciousness, “mental noise” often results. This mental noise arises from all the guessing, speculation, remembering, confusion, and so on that seems to regularly a part of every human’s mental life. ERV was developed with the idea that deliberately trying to come as close to an unconscious state as one can while still maintaining just enough awareness to respond to the monitor should make it easier to detect subtle remote viewing impressions with less mental noise.

Such a modality is very close to what was practiced by the “sleeping prophet,” Edgar Cayce, who would enter a hypnagogic sleep state before medically diagnosing patients and prescribing cures (with startling success), only to manifest amnesia after returning to waking consciousness. The infamous Brazilian psychic surgeon Arigo likewise performed his work in a state of trance. Like Cayce, he manifested amnesia after his performances. North explains that Arigo

would treat people for hours, yet after he was finished, he claimed that he remembered nothing. He wrote long, complicated medical prescriptions in a matter of half a minute, while staring blankly into space.8

Examples could be multiplied of the association of trance states with psychic functioning. The Irwin and Watt textbook notes that there is “substantial evidence” that success in ESP experiments is positively correlated with ASCs like “hypnosis, sensory (perceptual) deprivation or the ganzfeld, meditation, progressive relaxation, hypnagogic states, [and] dreaming.”9 Furthermore, it has been observed that spontaneous episodes of ESP are more common among those who exhibit “A recurrent desire to engage in absorbed mentation.”10 Moreover, retrocognition is associated with “dream-like” and “trance-like” states,11 while psychokinesis (PK) shows some connection with “a feeling of dissociation from the self” and “the suspension of the intellect.”12 Energy healers are known for engaging in “preparatory exercises” designed to conduct themselves into an “altered reality.” As Irwin and Watt note, “some healers are able to enter an absorbed state very rapidly or are habitually in such a state,” and many of them “are able to achieve high absorption in their own mentation.”13

The prolific parapsychologist Loyd Auerbach has reported that “my best psychic state appears to be boredom,” and he relates a poignant instance of his own out-of-body “bilocation” into a friend’s living room while in such a mental state.14 This correlates to “Informal observations [which] point to the importance of mental relaxation and passive attention rather than concentration” in the success of psychic metal benders.15

Death: An Extreme “Loosening” of the Soul

Trance, of course, is only one form of “loosening” from the body. And perhaps some of the strongest support for Wiesinger’s hypothesis lies in End-of-Life Experiences (ELEs), including Deathbed Visions (DBVs), Terminal Lucidity (TL), and Near-Death Experiences (NDEs).

To return to Wiesinger’s citation of the Stoic Posidonius:

The body of the sleeper then lies there as one dead, but the soul lives in the fullness of its power. This is much more true after death when it has completely left the body. That is why at the approach of death its divinity (= spirituality) is shown forth in a still higher degree, for men who are sick unto death see the approach of death, so that images of the dead appear to them (pp. 40–41)

In a previous post, I included a citation from Gregory the Great’s Dialogues (4:26–27), where it is recognized that “people so often make predictions when they are at the point of death,” which, Gregory says, is sometimes performed through the soul’s own “subtle power.” In A Magical World, I make mention that both John Knox and his mentor George Wishart made accurate prophecies at the time of their impending deaths.16

According to Wiesinger’s theory, this “deathbed clairvoyance” may be due to the soul’s beginning of separation from the body. Deathbed experiences are liminal moments—one is passing from one realm to another, and the spiritual component of the soul may then experience an abnormal ability to exercise its abilities.

Chapter 7 of A Magical World explored the evidence for preternatural information being derived from Near-Death Experiences, and it would seem that this more extreme “loosening” from the body is exactly what is taking place. In the case of Terminal Lucidity, dementia patients seem to regain their cognitive function in the moments leading up to death, something difficult to explain on a naturalistic basis, but which fits neatly with the idea that the soul is being “disencumbered” from the limits of the physical brain.

Conclusion

While there there may be some anomalies that don’t fit neatly into Wiesinger’s paradigm (e.g., people who exhibit paranormal abilities without a noticeable state of trance), it does have tremendous explanatory power overall, and it should be considered in any evaluation of preternatural gifts, both inside and outside Christian contexts.

In a follow-up article, I will address some of the practical takeaways from this model for Christians: Does the Holy Spirit use states of trance? Should one pursue development of the soul’s “powers”? What are the dangers in doing so? Does Wiesinger’s “fallen nature” theory of psychic powers hold up? Did the ancient Israelites and early Christians engage in trance and ecstasy?

Read part 2 here and part 3 here.

Harvey J. Irwin and Caroline A. Watt, An Introduction to Parapsychology, fifth ed., (Jefferson; London: McFarland & Co., 2007), 124. This statement is attributed to Michael Scriven.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 124. “The point of Scriven’s assessment of parapsychology . . . is that the field lacks what could be called an agreed theory.”

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 125–127.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 124.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, p. 137.

Wiesinger (on the same page) writes: “Writers who ascribe everything to demoniac intervention . . . argue as follows: there are certain manifestations for which there is no natural explanation, and since they cannot be ascribed to the intervention of God or the angels or to the dead, there remains only one possible author, and that is the devil.”

Tart’s landmark book, Altered States of Consciousness, was first published in 1969.

Gary North, Unholy Spirits: Occultism and New Age Humanism (Tyler: Institute for Christian Economics, 1994), 234.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 71.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 79.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 85.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 98.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 112.

Loyd Auerbach, ESP, Hauntings and Poltergeists: A Parapsychologist’s Handbook (Independent, 2015), Chapter 1.

Irwin and Watt, Parapsychology, 120.

Matthew McGuire, A Magical World: How the Bible Makes Sense of the Supernatural (Independent, 2024), 133.

Hi Matthew,

I came across your Substack in a rather roundabout way. While going through my Kindle notes for Diary of an American Exorcist, I noticed a reference to Alois Wiesinger. Curiosity led me to Goodreads, where I started reading the comments and eventually stumbled upon your reviews. I haven't finished reading this article yet, but it's absolutely fascinating! I subscribed and look forward to reading more of your work.

Best regards,

JRF