C.S. Lewis on Ghosts: An Anthology

Phantasmal Selections from Lewis' Letters, Experiences, and Fiction

In the “Ghosts” Appendix to A Magical World, I related the alleged apparition of the freshly deceased C.S. Lewis to New Testament scholar J.B. Phillips, in addition to Lewis’ own remarks about experiencing the presence of his late wife. I further cited some key passages from The Great Divorce to suggest that Lewis may have tacitly recognized a temporary ghostly existence as one possibility of the status animarum post mortem, as he once called it.1

The present article will be a selected anthology of comments that Lewis made during his lifetime on the subject of ghosts. I make no claim to be exhaustive nor to be certain of when Lewis exhibits a real belief versus a mere reference to popular tradition.2 This may be seen, for instance, in his use of the “haunted house” imagery in the opening of Perelandra to invoke a sense of dread, or his use of “ghost” imagery in The Problem of Pain to describe the “numinous.” In both cases, Lewis is simply using popular categories to capture a feeling rather than to make a statement on the real ontology of ghosts or haunted houses.

Due care, then, should be exercised when drawing from his published non-fiction, private letters, and (most of all) his fiction. Furthermore, one must allow for Lewis’ own development on the topic across the years, another point on which I claim no expertise.

Caveats aside, I expect it will be helpful (and enjoyable) to collate a number of his comments on this topic into one resource.

Personal Experience

Early Childhood

Whatever role it may have played in his later beliefs, Lewis tells us that he suffered from a childhood riddled with nightmares of ghosts and (worse) insects:

I suffered too much from night-fears myself in childhood to undervalue this objection. I would not wish to heat the fires of that private hell for any child. On the other hand, none of my fears came from fairy tales. Giant insects were my specialty, with ghosts a bad second. (“On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” 1952)

Again:

My bad dreams were of two kinds, those about spectres and those about insects. The second were, beyond comparison, the worse; to this day I would rather meet a ghost than a tarantula. (Surprised by Joy, 1955)

A Ghostly Dream

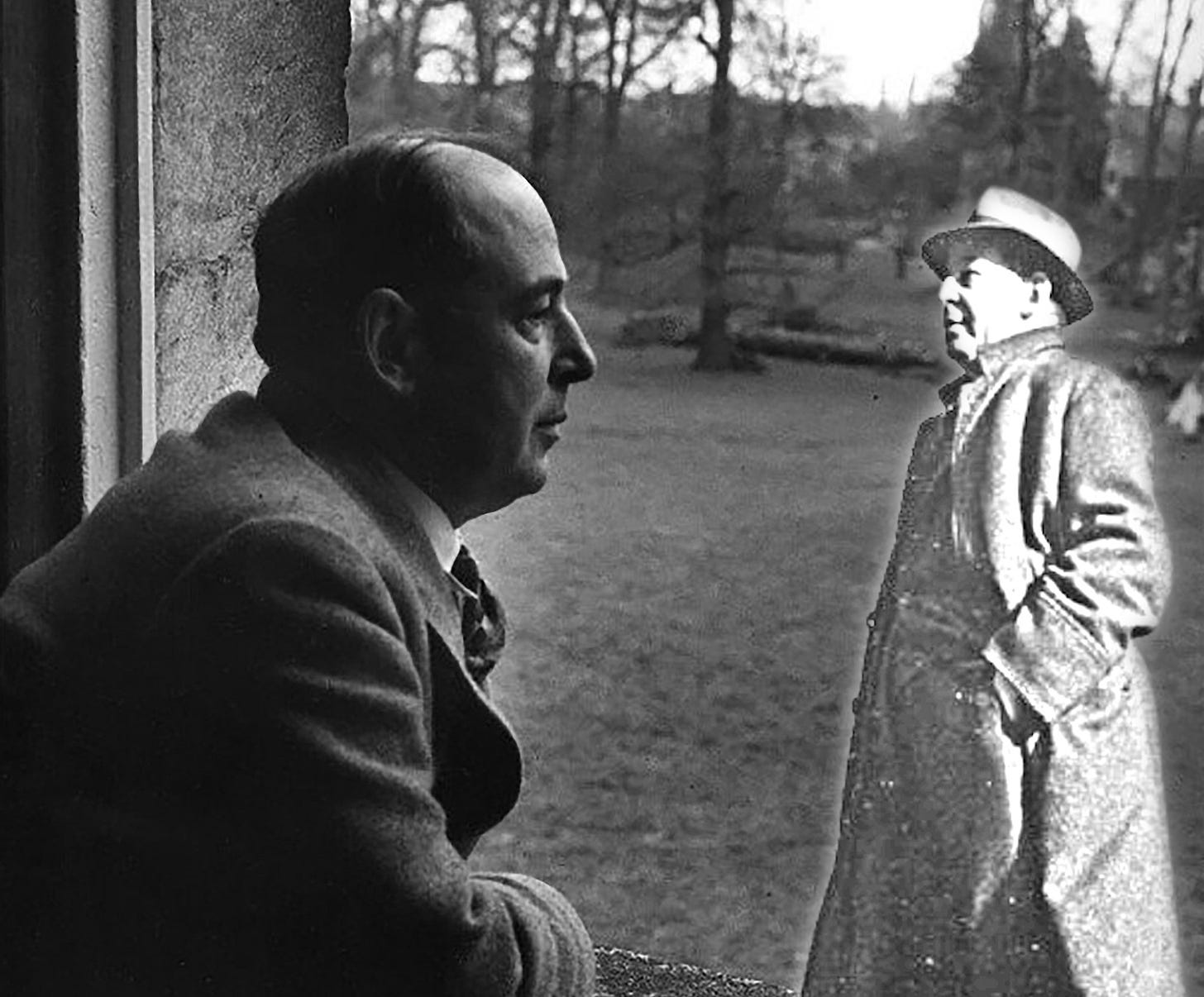

In a letter to Arthur Greeves, Lewis shares with his childhood friend and lifetime correspondent a recent dream about his father, who had died the previous year (1929).

The most interesting thing since I last wrote is a dream I had about my father. As a rule dreams about the dead fall into two distinct classes. (a) Those in wh. one simply forgets that the person has died (b) Those in which the dead appears as a bogey. My dream belonged to neither. I was in the dining room in Little Lea, with all the gasses lit and talking to my father. I knew perfectly well that he had died, and presently put out my hand and touched him. He felt warm and solid. I said ‘But of course this body must be only an appearance. You can’t really have a body now.’

He explained that it was only an appearance, and our conversation which was cheerful and friendly, but not solemn or emotional, drifted off onto other topics. I then went over to fetch you . . . . when you, in a voice of suppressed anxiety, said ‘Oh no, Jack. It’s just that you’ve been thinking about him and you’ve imagined he’s there.’

Till that moment everything had been pleasant and homely: but suddenly, as your words made me see the whole adventure from outside, as I realised how it would sound if repeated that I had been TALKING TO A DEAD MAN, the thing wh. had been SO normal in the experiencing it, rose up with such retrospective horror that the nightmare feeling flared up and I woke in terror. The dream seems to me a good idea of what might v. probably happen if one really met a ghost. At least I sometimes hope so. (Letter to Arthur Greeves, 15 September 1930)

Dreams of the recently deceased are a well-documented aspect of the phenomenon known as After-Death Communications (ADCs). However, this particular case offers no “veridical” information which would rule out a mere projection of the imagination. Such cases, such as one related by Saint Augustine (De Cura Pro Mortuis 11.13–13.16), indicate that we should not dismiss all realistic dreams of the deceased as fantasy.

Haunted Lodgings

In a few private letters, Lewis makes mention that he is writing from a “haunted” location. While convalescing from war wounds in Ashton Court in Bristol, a pre-conversion Lewis writes to his father:

The house here is the survival, tho’ altered by continual rebuilding, of a thirteenth-century castle: the greater part is now stucco work of the worst Victorian period (à la Norwood Towers) but we have one or two fine old paintings and a ghost. I haven’t met it yet and have not much hope to—indeed if poor Johnson’s ghost would come walking into the lonely writing room this minute, I should be glad enough. (Letter to Albert Lewis, 29 June 1918)

It escapes me whether his phrase “have not much hope to [meet the ghost]” refers to his preference not to have such a numinous encounter or, alternatively, his chagrin that his chances of doing so were low. Either way, however, the phrase may simply be written tongue-in-cheek.

Much later in Life, Lewis tells of another haunted location he visited:

Fairies–the people of the Shidhe (pronounced Shee)—are still believed in many parts of Ireland and greatly feared. I stayed at a lovely bungalow in Co. Louth where the wood was said to be haunted by a ghost and by fairies. But it was the latter who kept the country people away. Which gives you the point of view—a ghost much less alarming than a fairy. (Letter to Mary Willis Shelburne, 9 October 1954)

This instance, of course, offers no comment from Lewis on his own beliefs, but it shows that it was a worthy subject of discourse for him. Further, one does not get the sense that Lewis is in any way sneering at Irish superstition (he was a native of Ulster, after all). The tone is one of curiosity.

An Absence of Apparitions

As of the year 1947, Lewis reports that he had only met one person who claimed to have seen a ghost:

In all my life I have met only one person who claims to have seen a ghost. And the interesting thing about the story is that that person disbelieved in the immortal soul before she saw the ghost and still disbelieves after seeing it. She says that what she saw must have been an illusion or a trick of the nerves. And obviously she may be right. Seeing is not believing. (Miracles, 1947)

Since Miracles was revised in 1960, we might also venture to suppose that this paragraph remained true at the later date as well. Assuming Lewis included himself in his survey, he appears not to have been visited by any (recognizable) apparitions up until a mere three or so years before his death. As it happens, however, his wife passed away in July of the very same year, bringing us to our next story.

“An Extreme and Cheerful Intimacy”

In his pseudonymous A Grief Observed (1961), Lewis pulls back the curtain on the bereavement that followed the death of his wife, Joy Davidman. He records moments when he felt from her “an instantaneous, unanswerable impression. To say it was like a meeting would be going too far. Yet there was that in it which tempts one to use those words.” Later he writes of “an extreme and cheerful intimacy” felt between his mind and hers. While this story, like others, could be attributed to psychological projection, I find it curious that Joy had expressed an intention to visit Lewis after her death:

Once very near the end I said, ‘If you can—if it is allowed—come to me when I too am on my death bed.’

‘Allowed!’ she said, ‘Heaven would have a job to hold me; and as for Hell, I’d break it into bits.’

She knew she was speaking a kind of mythological language, with even an element of comedy in it. There was a twinkle as well as a tear in her eye. But there was no myth and no joke about the will, deeper than any feeling, that flashed through her.

This episode with Joy, whether objective or subjective, exhibits some similarities with Lewis’ feelings after the death of Charles Williams, his beloved friend and (likely) the archetype for Elwin Ransom in his science fiction trilogy.3

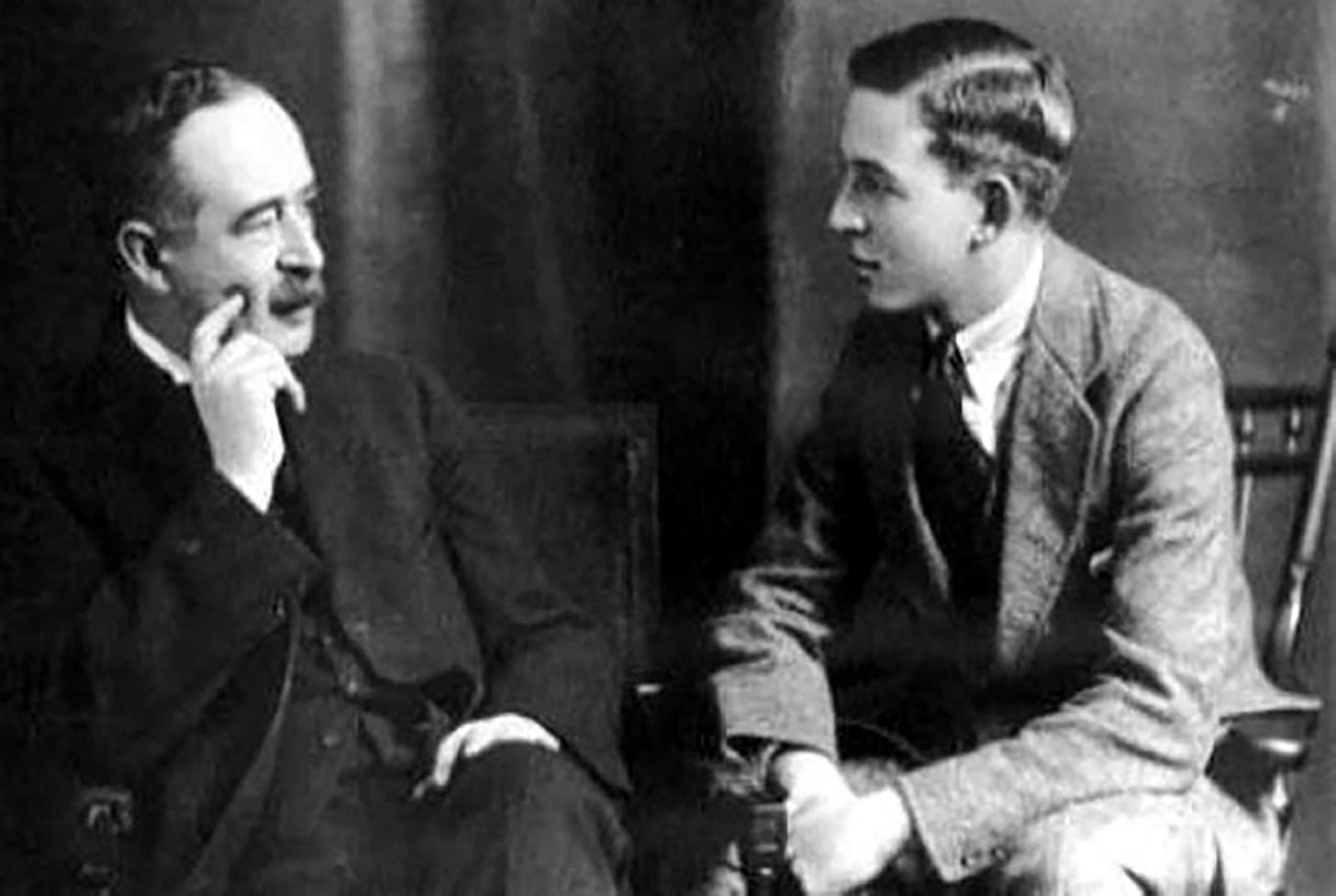

The Death of Charles Williams

Lewis wrote of a shift in his own attitude toward death and his feeling of Williams’ presence to several friends in the wake of this fellow Inkling’s death. Three days after the death, Lewis wrote:

This, the first really severe loss I have suffered, has (a) Given a corroboration to my belief in immortality such as I never dreamed of. It is almost tangible now. (b) Swept away all my old feelings of mere horror and disgust at funerals, coffins, graves etc. If need had been I think I cd have handled that corpse with hardly any unpleasant sensations. (c) Greatly reduced my feelings about ghosts. I think (but who knows?) that I shd be, tho afraid, more pleased than afraid, if his turned up. In fact, all v. curious. Great pain but no mere depression. . . . (Letter to Owen Barfield 18 May 1945)

Lewis, it seems, was hoping to have a run-in with the ghost of Charles Williams! It doesn’t strike me as obvious that he is writing tongue-in-cheek here.

To Williams’ widow, he wrote:

My friendship is not ended. His death has had the very unexpected effect of making death itself look quite different. I believe in the next life ten times more strongly than I did. At moments it seems almost tangible. Mr. Dyson, on the day of the funeral, summed up what many of us felt, ‘It is not blasphemous’, he said ‘To believe that what was true of Our Lord is, in its less degree, true of all who are in Him. They go away in order to be with us in a new way, even closer than before.’ A month ago I wd. have called this silly sentiment. Now I know better. He seems, in some indefinable way, to be all around us now. I do not doubt he is doing and will do for us all sorts of things he could not have done while in the body. (Letter to Florence (Michal) Williams, 22 May 1945)

A few days later, he repeats these thoughts to another friend:

Death has done nothing to my idea of him, but he has done—oh, I can’t say what—to my idea of death. It has made the next world much more real and palpable. We all feel the same. How one lives and learns. I have often heard of widows and bereaved mothers who ‘felt that “he” was now nearer to them than while in the body’ and always thought it a sentimental hyperbole. I know better now. As someone said to me just after the funeral ‘It is not blasphemous to believe that what is true of Our Lord is true in their degree of all who are His. They go away in order to return in a new mode. It is expedient for us that they do. It is thus and thus only that in each case the Comforter comes.’ May one accept this? (Letter to Sister Penelope, 28 May 1945)

And again, to a third female interlocutor:

It [Williams’ death] has increased enormously one’s faith in the next life and I can’t help feeling him all over the place. I can’t put it into words: I never knew the death of a good man cd. itself do so much good. I don’t mean there isn’t pain, pain in plenty: but not dull, sullen, sickening, drab, resentful pain. (Letter to Anne Ridler, 3 June 1945)

Lewis’ experiences in 1945, as captured above, were deeply influential in his imagination of the active and aware life of the “blessed dead.” In Lewis’ mind, Williams was not sectioned away in a hermetically sealed chamber of Hades, but rather actively providing comfort, presence, and assistance to his beloved friends still in the flesh.

It would not be a stretch to assume, then, that Lewis’ petition that Joy visit him posthumously was partly informed by his experience of Williams’ presence in 1945. Lewis was also reported to have entertained the idea that the deceased may undergo a period of lingering as a sort of post-mortem bereavement process. Sheldon Vanauken once shared with Lewis a realistic dream that he experienced of his wife, Davy, following her death. He writes:

[Lewis] was thoughtful about the idea of the dead undergoing bereavement, and then said he could see no reason why it might not be so. . . . One of us suggested, then or later, that if the dead do stay with us for a time, it might be allowed partly so that we may hold on to something of their reality. Lewis, who had evidently thought further about the idea of the dead also experiencing sorrow, brought it up again, saying that the soul’s progress towards the Eternal Being might necessitate the experience of bereavement, either in life or afterwards. (A Severe Mercy, Epilogue, recounting a conversation with Lewis in 1957)

Spiritualism

Lewis’ thoughts on the presence of the dead during a bereavement period may lead one to suspect that he would have entertained (or at least tolerated) the practices of Spiritualism—wherein a medium or channeler would make contact with a lost loved one to provide solace. From beginning to end, however, Lewis was firmly opposed to such practices, on a number of grounds.

Prior to his conversion, Lewis exhibited a marked skepticism toward the behavior of the “ghosts” of seance rooms. One diary entry reads:

An excited conversation between the Doc and Mrs S. on spiritualism. D retired as she felt she couldn’t refrain from sceptical interruptions. I was less kind and asked why ghosts always spoke as though they belonged to the lower middle classes. We talked a little of psychoanalysis, condemning Freud . . . (Diary, 26 May 1922)

A perennial critique of the messages conveyed by mediums is that of their vague, banal character. Few of these afterlife insights amounted to anything better what you might find from a fortune cookie. Lewis carried on this general opinion into later life. As Walter Hooper tells us:

[Lewis] distrusted Spiritualism and believed that the dead had far more worthwhile things to do than send ‘messages’. ‘Will anyone deny,’ he wrote in ‘Religion Without Dogma?’ [1946], ‘that the vast majority of spirit messages sink pitiably below the best that has been thought and said even in this world?—that in most of them we find a banality and provincialism, a paradoxical union of the prim with the enthusiastic, of flatness and gush, which would suggest that the souls of the moderately respectable are in the keeping of Annie Besant and Martin Tupper?’ (The Dark Tower, editor’s postscript)

This can also be seen in one letter to his brother:

Part of Thursday afternoon I spent with unusual pleasure in the dark, pleasantly smelling, warmth of the old library with a slow dampish snow falling outside-flakes the size of matchboxes. I had gone in to look for something quite different, but became intrigued by the works of Dr Dee, a mysterious magician and astrologer of Queen Elizabeth’s time. The interesting thing about this was the fact that it was so uninteresting: I mean that the spirit conversations displayed, so far as I could see from turning over a few pages, just exactly the same fatuity wh. one observes in those recorded by modern spiritualists. What can be the explanation of this? I suppose that both are hallucinations resulting from the same kind of mental weakness which, at all periods, produces the same rubbish. (Letter to Warnie Lewis, 28 January 1940)

Lewis, then, seems to think these “ghostly messages” arise from mere hallucinations (when not from charlatans). Yet he adds a curious possibility further in the letter:

One can’t help, however, toying with the hypothesis that there are all real spirits in the case, and that we tap either a ghostly college of buffoons or a ghostly home for imbeciles.

This latter possibility hints at the notion of mediums encountering a disturbed, “unquiet” population of deceased humans. If this be the case, there is no reason to suppose that such a maladjusted population would have anything insightful or trustworthy to tell us about the hereafter. Thus, there remains no legitimate reason to seek after mediums.

Furthermore, on theological grounds, Lewis took issue with the very ethos of Spiritualism:

You are quite right to keep clear of the Spiritualists. All that is an effort to cancel death, to go on getting a pale phantom of the same sort of intercourse with our dear ones which we had when they and we were members of the same world. But we must submit to death, embrace the cross.

I think the purpose of the separation is to help us to turn what is merely natural and instinctive affection into real spiritual love of them in Christ. Not that natural affection isn’t good & innocent, but it is merely natural—and therefore must first be crucified before it can rise again. Those who try to escape the crucifixion fall in either with charlatans or with delusions from hell: spiritualism often drives people mad. Of course we should pray for our dead as I’m sure they do for us. (Letter to Mrs. Percival Wiseman, 20 March 1944)

Lewis believed that a sort of love and connection continued beyond the grave, but that we should not attempt to force the departed to return to their earlier form of existence. He writes to one new widow:

Comfort will come as you master that work, as you learn more & more to be a channel of God’s grace to your husband (and perhaps to others): not for trying to get back the conditions you had in the lower form.

Keep clear of Psychical Researchers (Letter to Phyllis Elinor Sandeman, 31 December 1953)

His caution against “Psychical Researchers” is probably directed at that cohort which studied mediumship, not necessarily those who studied ESP abilities in general. Lewis seems to take J.B. Rhine’s laboratory work at face value:

Rhein’s [sic] experiments on extra-sensory perception are taken seriously and not generally suspected of containing any fraud, but the question of what they prove is still highly controversial. (Letter to Mary van Deusen, 14 December 1958)

Later in the same letter, he expands upon his Christian misgivings on Spiritualism:

I don’t see anything sinful in speculating about the perceptions of the apostles, tho’ I doubt if we have evidence enough to make it very useful. But spiritualistic practices are a very different thing. First, the record of proved fraud in such matters is surely very big and black: there’s money in mediumship! Second, it very often has extremely bad effects on those who dabble in it; even insanity. And thirdly, most supposed communications through mediums are the silliest, sentimental, or even incoherent, twaddle. Why go to spirits to hear bosh when you can hear sense from quite a lot of your neighbours?

But I think the practice is a sin as well as folly. Necromancy (commerce with the dead) is strictly forbidden in the Old Testament, isn’t it? The New frowns on any excessive and irregular interest even in angels. And the whole tradition of Christendom is dead against it. I wd. be shocked at any Christian’s being, or consulting, a medium.

It is Resurrection, not ‘survival’ that we think of, and the spirit that concerns us is the Holy Spirit! I’d give Mr. A. Ford [a prominent Spiritualist minister] a wide berth myself.

Here we see a combination of Lewis’ intellectual and theological objections to Spiritualism. Readers should not take the last sentence of his to imply that he disbelieved in an intermediate state prior to the Resurrection—the previous quotations in this article demonstrate such a belief—only that the Christian hope of the New Testament emphasizes the Resurrection as the ultimate telos for the faithful.

These above comments lead us to consider what else Lewis said about the “life of the dead” on theological grounds.

Theology

I have not been able to find any explicit theological statement from Lewis on the idea of ghostly existence or apparitions. That said, he certainly referenced them and speculated about them. We are told some sparse details of a particular Inklings meeting in one of Tolkien’s letters:

But there was some quite interesting stuff. A short play on Jason and Medea by Barfield, 2 excellent sonnets sent by a young poet to C.S.L.; and some illuminating discussion of ‘ghosts’ (The Collected Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter to Christopher Tolkien 24 November 1944)

The letter refers to a meeting “yesterday” (November 23rd), where Tolkien, the Lewis brothers, and Owen Barfield were all present. I would love to have been a fly on the wall for this conversation, but, alas, I have not been able to trace any further information on this meeting.

In Miracles, Lewis recognized that, in the worldview of the Old Testament, “shades could return and appear to the living,” citing the example of Samuel’s ghost.4 Yet, he also saw such ghostly existence as a privation of sorts:

Ghosts must be pictured, if we are to picture them at all, as shadowy and tenuous, for ghosts are half-men, one element abstracted from a creature that ought to have flesh. . . .

the human dead, when glorified in Christ, cease to be ‘ghosts’ and become ‘saints’. The difference of atmosphere which even now surrounds the words ‘I saw a ghost’ and the words ‘I saw a saint’—all the pallor and insubstantiality of the one, all the gold and blue of the other—contains more wisdom than whole libraries of ‘religion’. (Miracles, Chapter 11)

Christians, who are identified with the risen Christ, can expect a form of glorification in the after-death state. Lewis refers to this transformation as “becoming a saint.” As an editorial comment, this framework seems to allow for a category of both the “unquiet dead” (traditional ghosts) as well as the “blessed dead” (saints).

Speaking of saints, Lewis did not consider the high church practice of invoking the saints to be on the same level of error as Spiritualism, but he had significant reservations about it nonetheless:

Hail Marys raise a doctrinal question: whether it is lawful to address devotions to any creature, however holy. My own view would be that a salute to any saint (or angel) cannot in itself be wrong any more than taking off one’s hat to a friend: but that there is always some danger lest such practices start one on the road to a state (sometimes found in R.C.’s) where the B.V.M. [Blessed Virgin Mary] is treated really as a deity and even becomes the centre of the religion. I therefore think that such salutes are better avoided. And if the Blessed Virgin is as good as the best mothers I have known, she does not want any of the attention which might have gone to her Son diverted to herself. (Letter to Mary van Deusen, 26 June 1952)

Thus, Lewis seemed open to the working of the saints on our behalf, and even the possibility of them appearing to us, but he was not keen on direct invocation or devotion.

Fiction

At this juncture, I think it is appropriate to include some of Lewis’ references to ghosts in his fictional works. Walter Hooper, after remarking on a ghostly account included in Lewis’ unfinished work The Dark Tower, writes:

This extraordinary ghost-story is not, perhaps, unbelievable, and I understand that Lewis did believe it till, some time later, his friend Dr R. E. Havard mentioned having seen a retraction of it by one of the ladies involved. (The Dark Tower, editor’s postscript)

That Lewis saw fit to incorporate details of a report like this—a report that he appeared to believe at the time—into his fiction reminds us that he often blurred the lines between the marvelous aspects of the real world and the mere romantic exaggerations of his fictional worlds. All the same, we should keep in mind Hooper’s warning in the same section:

While The Dark Tower tells us a great deal about C. S. Lewis’s reflections on time, I think it would be a mistake to suppose that fact and fiction, so finely blended in his story, were not clearly distinguished in his mind.

Narnian Ghost Geography

Though offering meagre evidence of what Lewis really thought about ghosts, two accounts in the Narnia series depict an understanding of popular “ghost geography.” That is to say: a ghost is a being from one dimension making an appearance in another. In other words, a ghost is a visitation of a being outside its proper domain. Consider the aside offered by the now-deceased Prince Caspian in Chapter 16 of The Silver Chair (1953):

“Oh,” said Caspian. “I see what’s bothering you. You think I’m a ghost, or some nonsense. But don’t you see? I would be that if I appeared in Narnia now: because I don’t belong there any more. But one can’t be a ghost in one’s own country. I might be a ghost if I got into your world. I don’t know. But I suppose it isn’t yours either, now you’re here.”

Similarly, in Chapter 4 of The Last Battle (1956), we see King Tirian appearing as a ghost when his consciousness is projected into England, where the human protagonists of the earlier books react “as if they saw a ghost,” variously speculating whether he be “a phantom or a dream” before he eventually fades and vanishes before their eyes. While this is not a case of a deceased individual returning to the land of the living, it is a case of a person traversing outside his proper domain. Hence, he appears with all the qualities of a “ghost.”

Wither’s Apparition

In Chapter 10 of That Hideous Strength (1945), Mark Studdock finds himself confronted with a ghostly antagonist:

Now he was past the road; he was in the belt of trees. Scarcely a minute had passed since he had left the DD’s office and no one had overtaken him. But yesterday’s adventure was happening over again. A tall, stooped, shuffling, creaking figure, humming a tune, barred his way. Mark had never fought. Ancestral impulses lodged in his body—that body which was in so many ways wiser than his mind—directed the blow which he aimed at the head of his senile obstructor. But there was no impact. The shape had suddenly vanished.

So far, a classic apparition and vanishing. But the following paragraph may give some additional insight into Lewis’ mind:

Those who know best were never fully agreed as to the explanation of this episode. It may have been that Mark, both then and on the previous day, being over-wrought, saw a hallucination of Wither where Wither was not. It may be that the continual appearance of Wither which at almost all hours haunted so many rooms and corridors of Belbury was (in one well-verified sense of the word) a ghost—one of those sensory impressions which a strong personality in its last decay can imprint, most commonly after death but sometimes before it, on the very structure of a building, and which are removed not by exorcism but by architectural alterations. Or it may, after all, be that souls who have lost the intellectual good do indeed receive in return, and for a short period, the vain privilege of thus reproducing themselves in many places as wraiths. At any rate the thing, whatever it was, vanished

After acknowledging the ever-present possibility of “a hallucination,” Lewis shows that he is aware of the “psychic imprint” theory of hauntings, as he describes how a “ghost” can be created by “a strong personality” and become imprinted onto a structure or landscape. The Psi Encyclopedia summarizes findings from the field of parapsychology:

The repeated appearance of an apparition or apparitions in a particular house or area is described as a haunting. Haunting apparitions frequently act in a repetitive and robotic manner, compulsively repeating the a sequence of apparently meaningless and unmotivated actions. They usually appear oblivious to people in their presence.

Lewis distinguishes between this type of “non-interactive” apparition and a real ghost, which he calls a “wraith” who is temporarily consigned to a ghostly existence by virtue of having “lost the intellectual good.”

The above excerpt, however it may add to the fictional narrative itself, tells us that Lewis was cognizant of the different categories of “ghosts” known to popular lore and scientific study. But I also wonder whether his statement that the fictional characters “were never fully agreed as to the explanation” may tell us something about his own mindset on the topic as a whole. He may have remained uncertain himself as to the best explanation for ghost phenomena. This is perhaps corroborated in another letter, where, writing about the implications of Merlin’s resurrection in That Hideous Strength, Lewis writes:

Whatever the normal status animarum post mortem may be, it is feigned that this one man was exempted from it and returned just as he was. (I know they don’t really: I was writing a story). (Letter to Cecil and Daphne Harwood, 11 September 1945)

Lewis’ use of the phrase “Whatever the normal status animarum post mortem may be” could suggest an openness and curiosity as to the precise nature of the immediate post-mortem state of the soul. Perhaps we aren’t given all the details in Scripture. Perhaps this threshold of life and death is individualized to each person.

The Unquiet Dead Visit Earth

Lewis nowhere speaks more about ghosts than in The Great Divorce (1945), a fictional dream of the afterlife. In his vision of the “grey town”—an intermediate state for souls—he depicts the mischievous and self-absorbed ghosts that

prefer taking trips back to Earth. They go and play tricks on the poor daft women ye call mediums. They go and try to assert their ownership of some house that once belonged to them: and then ye get what’s called a Haunting. Or they go to spy on their children. Or literary ghosts hang about public libraries to see if anyone’s still reading their books.

It is curious that this brief description not only describes the archetypal ghost motifs of unfinished business or lingering attachment to the world but also provides a Christian framework within which we might make sense of them. These “unquiet dead” may be the same category of “wraiths” spoken of in That Hideous Strength.

In A Magical World, I interpreted this passaged as “Lewis’ tacit recognition that the departed pay visits to the land of the living, though often under inauspicious circumstances.” I maintain this view, though I must close this section on Lewis’ fiction with a warning from the closing section of The Great Divorce:

‘Do not ask of a vision in a dream more than a vision in a dream can give.’

‘A dream? Then—then—am I not really here, Sir?’

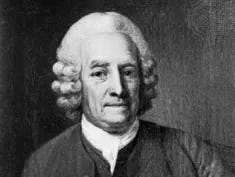

‘No, Son,’ said he kindly, taking my hand in his. ‘It is not so good as that. The bitter drink of death is still before you. Ye are only dreaming. And if ye come to tell of what ye have seen, make it plain that it was but a dream. See ye make it very plain. Give no poor fool the pretext to think ye are claiming knowledge of what no mortal knows. I’ll have no Swedenborgs and no Vale Owens among my children.’

‘God forbid, Sir,’ said I, trying to look very wise.

‘He has forbidden it. That’s what I’m telling ye.’

The stark censure of visionary Emanuel Swedenborg and Spiritualist George Vale Owen tell us that Lewis had an anti-Promethean disposition. Some things are not for us to fully know on this side of the hereafter.

A Premeditated Haunting

As we approach the end of Lewis’ earthly life, I want to draw attention to a curious farewell letter that Lewis wrote to his colleagues at Cambridge less than a month before his death:

Dear Master and Colleagues,

The ghosts of the wicked old women in Pope ‘haunt the places where their honour died’. I am more fortunate, for I shall haunt the place whence the most valued of my honours came.

I am constantly with you in imagination. If in some twilit hour anyone sees a bald and bulky spectre in the Combination Room or the garden, don’t get Simon to exorcise it, for it is a harmless wraith and means nothing but good. (Letter to the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, 25 October 1963)

While this comment smells of cheek, one wonders if Lewis had a wistful longing to revisit his cherished colleagues and college grounds from beyond the grave. If there was any real hope behind his earlier request that Joy would pay him a posthumous visit, then perhaps there was some real intentionality undergirding this wish to “haunt” his friends. And indeed, at least one colleague of his reported just such a visit.

As noted in the opening paragraph, the cherished New Testament scholar and translator J.B. Phillips reported a surprise visit from “Jack” a few days after the fateful events of 11/22/63. As he recounts it:

A few days after his death, while I was watching television, he “appeared” sitting in a chair within a few feet of me, and spoke a few words which were particularly relevant to the difficult circumstances through which I was passing. He was ruddier in complexion than ever, grinning all over his face and, as the old-fashioned saying has it, positively glowing with health. The interesting thing to me was that I had not been thinking about him at all. I was neither alarmed nor surprised . . . . He was just there—“large as life and twice as natural”! A week later, this time when I was in bed reading before going to sleep, he appeared again, even more rosily radiant than before, and repeated to me the same message, which was very important to me at the time. I was a little puzzled by this, and I mentioned it to a certain saintly Bishop . . . . His reply was, “My dear J. . . ., this sort of thing is happening all the time”. (Ring of Truth, pp. 89–90)

Maybe, just maybe, Lewis ran a few post-mortem errands before “going on to the mountains” of the Heavenly abode.

In one letter, Lewis shows himself to be both open and aware of such “neo-mortal” communications:

I don’t think there is anything superstitious in your story about the Voice. These visions or ‘auditions’ at the moment of death are all v. well attested: quite in a different category from ordinary ghost stories. (Letter to Mary Willis Shelburne, 1 January 1954)

Sadly, I have been unsuccessful in locating the preceding letter from Mrs. Shelburne. It is ambiguous as to whether Shelburne’s loved one experienced this “Voice” at the time of his or her death (a Deathbed Vision or DBV), or, alternatively whether Shelburne herself heard the “Voice” of a newly deceased loved one (an After-Death Communication or ADC). In either case, Lewis seems to react positively to this sort of comfort from beyond.

Takeaways

As I said, I am no authority on Lewis and would not pretend expertise in interpreting his various statements on ghosts. That said, I think there are a few statements we can make based on this survey. I suggest that Lewis believed the following:

People may at times “linger” after death. This can be either an “inauspicious lingering” of the unquiet dead, or an “auspicious lingering” of the blessed dead, perhaps on a “holy errand.”

The blessed dead are active and aware of life on earth, looking out for us in ways that we cannot imagine.

We should pray for the dead (though not summon them), as they pray for us.

End-of-life moments and the time immediately following death are “threshold” periods, where some form of contact between realms is sometimes experienced.

Though he enjoyed reporting his stays at haunted locations, hoped for post-mortem visitations, and spoke of the dead being involved in our lives, Lewis was not definitive on the subject. He would echo the Scriptural maxim that “the secret things belong to the Lord” (Deut. 29:29), and he would not want us to be too adamant about knowing the precise details of the status animarum post mortem.

Lest we end up like Archibald in The Great Divorce—so focused on proving post-mortem survival that he found no interest in God himself—Lewis would have faithful Christians “submit to death, [and] embrace the cross.”

Letter to Cecil and Daphne Harwood, 11 September 1945. Unless otherwise noted, all references to Lewis’ letters are taken from The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, 3 Vols., published by HarperOne. Diary entries are excerpted from All My Road Before Me: The Diary of C. S. Lewis, 1922–1927, published by Mariner Books. I have taken the liberty to adjust paragraph breaks.

E.g., Lewis’ use of the “haunted house” imagery in the opening of Perelandra to invoke a sense of dread, or his use of “ghost” imagery in The Problem of Pain to capture the sense of the “numinous.” Either example seems to be Lewis using popular categories to capture a feeling rather than to make a statement on the real ontology of haunted house or ghosts.

In an editor’s postscript to The Dark Tower (a unfinished work by C.S. Lewis, published posthumously), Walter Hooper writes: “In his ‘Reply to Professor Haldane’ Lewis says that the Ransom of That Hideous Strength (and presumably of Perelandra as well) is ‘to some extent a fancy portrait of a man I know, but not of me’, and Gervase Mathew believes that ‘man’ is almost certainly Charles Williams, whom Lewis was only just getting to know when he was writing The Dark Tower. Gervase Mathew was close to both men, and being in a position to observe Williams’s profound influence on Lewis, sees the Ransom of the last two romances as having grown into a kind of idealised Williams— but a Williams, I should venture to guess, underpinned by the steady brilliance and philological genius of Lewis’s other great friends, Owen Barfield and J. R. R. Tolkien.”

He also acknowledged the disciples’ belief in traditional ghost lore: “I don’t mean that they disbelieved in ghost-survival. On the contrary, they believed in it so firmly that, on more than one occasion, Christ had had to assure them that He was not a ghost. The point is that while believing in survival they yet regarded the Resurrection as something totally different and new” (“What Are We to Make of Jesus Christ?”).