“Is monasticism the only road to God?” Thomas asked abruptly.

“Of course not,” Father Maximos responded. “But it is one way.”1

Coming from an evangelical Protestant background, I did not grow up hearing much about monasticism. Unlike those of a more high-church tradition, our heroes of the faith did not include lonely hermits or ascetics. Instead, we were inspired with the stories of great missionaries like Brother Andrew or martyrs like Jim Elliot.

When the topic of monasticism arose, it was looked down upon as a post-biblical corruption of a more pure New Testament Christianity. We smiled favorably on Luther’s “liberation” of nuns and monks from their former vows and their re-dedication to faithful living in the “real world.”

The ascetic aspects of monasticism smelled of an implicit gnosticism—a denial of the goodness of creation so central to the Hebraic roots of Christianity (1 Tim. 4:4). Furthermore, those who would withdraw themselves from the multitudes of society were spiritually indulgent and self-serving, neglecting the “one another” commands to bless neighbor and brother alike. Calvin captures this attitude well when speaking of the early monastics:

It was a beautiful thing to forsake all their possessions and be without earthly care. But God prefers devoted care in ruling a household, where the devout householder, clear and free of all greed, ambition, and other lusts of the flesh, keeps before him the purpose of serving God in a definite calling. (Institutes 4.8.16)

On this view in which I was raised, monasticism “despised the ordinary ministry” which is explicitly willed by God in Scripture, and instead created a false “double Christianity” where monks feign a superior faithfulness over the laity. (Institutes 4.8.14)

And besides the Scriptural objections . . . the whole business just seemed too Catholic!

Ancient Perspectives

Further reflection on this subject over the years, however, has made me reconsider this dismissive conception of hermits and monasticism.

One of the primary influences behind this change in direction came from some of the heroes celebrated across all branches of Christianity (including those of the Reformation)—Saints Athanasius and Augustine. Both expressed deep admiration for the faith’s first major hermit.

Saint Anthony, who may be rightly called the “father of the desert fathers,” left societal life to dedicate himself to spiritual progress. His reputation abounded with stories of his personal holiness, prophetic abilities, and battles with demonic apparitions.

Famous for his intrepid defense of Nicene orthodoxy, Saint Athanasius had himself been a disciple of the infamous desert monk, eventually penning his biography. In the preface to said book, he drips with reverence for the life of this secluded saint:

Most willingly have I accepted the task you imposed; indeed, merely to call Anthony to mind is of great profit to me, and I know that, when you have heard about him, you will not content yourselves with admiring the man, but you will also wish to imitate his way of life, for the life of Anthony is for monks an adequate guide in asceticism (Life of Anthony, Preface)

Augustine, in his autobiography, twice speaks of the power of Anthony’s life on his own spiritual pilgrimage. He recalls the first time he heard tell of “Antony the Egpytian monk,” where he “stood amazed, hearing Thy wonderful works most fully attested, in times so recent, and almost in our own, wrought in the true Faith and Church Catholic” (Confessions 8.6).

He further recounts hearing the story of two high-class men who came across Anthony’s biography at a monastery “under the fostering care of Ambrose” in Milan. These two were so affected by the little book, that they devoted themselves to a life of total devotion to God, giving up on the ancient equivalent to the “rat race”—the vainglorious hope of “be[coming] the Emperor’s favorites.”

This account, says Augustine, was the means by which God “didst turn me round towards myself” and starkly revealed his sinful condition. (Confessions 8.6–7)

Coming to his most acute moment of conversion—the infamous tolle lege episode—Augustine partially credits his epiphany to the memory of Anthony’s own calling:

For I had heard of Antony, that coming in during the reading of the Gospel, he received the admonition, as if what was being read was spoken to him: Go, sell all that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven, and come and follow me: and by such oracle he was forthwith converted unto Thee. Eagerly then I returned to the place where Alypius was sitting; for there had I laid the volume of the Apostle when I arose thence. I seized, opened, and in silence read that section on which my eyes first fell: Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying; but put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh, in concupiscence. No further would I read; nor needed I: for instantly at the end of this sentence, by a light as it were of serenity infused into my heart, all the darkness of doubt vanished away (Confessions 8.12).

Few could be classified as further from gnostic dualism than Athanasius and Augustine, yet these men saw no conflict between Anthony’s lifestyle and the values of orthodox Christianity. To the contrary, they understood his spiritual example to be one worthy of imitation.

It should be noted that Calvin argued that there were several differences between the ancient monasticism, as described by Augustine, and that of his own day, writing that “our hooded friends . . . differ from [the early monastics] as much as apes from men” (Institutes 4.8.19).2

That said, Calvin rejected even the more pure forms of monasticism, with one editor noting that this was “One of the very few instances in which Calvin disapproves of an opinion of Augustine.”3

Though Calvin offers helpful cautions against rash vows, clericalism, and misinterpreted Scriptures, I have found myself agreeing with the ancients that some may be called to a legitimate vocation of monasticism.

The Doctrine of Vocation

“The Christian shoemaker does his duty not by putting little crosses on the shoes, but by making good shoes, because God is interested in good craftsmanship.” — Martin Luther

“Your perfection consists in living perfectly in the place, occupation and position in which God . . . has assigned to you.” —Josemaría Escrivá

Luther, Calvin, and many of their compatriots of the Reformation emphasized the doctrine of vocation—of living out God’s grace in whatever calling you have been assigned. Artisans, farmers, soldiers, and clergy were all to perform their duties “as to the Lord, and not unto men” (Col. 3:23).

This emphasis on the holiness of all vocations was one of the great contributions of the Reformed ethic, and it is something that later took hold of a number of Roman Catholics, such as the above-quoted founder of Opus Dei.

The doctrine of vocation is relevant to the question of monasticism. If some are called to a life of shoemaking, may not others be called to a life of prayer? If some have been assigned to manage wealth in a godly fashion, may not others be assigned to follow God in a life of poverty?

We find in Scripture a number of monastic trappings which are assigned to certain groups or individuals: poverty (Matt. 19:21), discomfort (Matt. 8:20), fasting (1 Kings 19:8), secluded prayer (Mark 1:35), vows (Num. 6), and celibacy (1 Cor. 7:7). Some of these are temporary (Num. 6), while others are long-term (Judges 13).

Monasticism, then, is simply a vocation that combines a number of these individual callings into one lifestyle. Considered rightly, it is not to be understood as ontologically superior to all other vocations (the monastic form of clericalism that Calvin fought), but it still remains a legitimate vocation itself.

Consider, for instance, the vocation of secluded prayer and intercession. We read in The Mountain of Silence of Elder Paisios’ reaction to news of the Gulf War:

he shut himself in his cell, cutting off all contact with visitors. That went on during the entire duration of the war. In fact, he intensified his prayers so that the war, as he told me later, would not get out of control and become even more destructive.

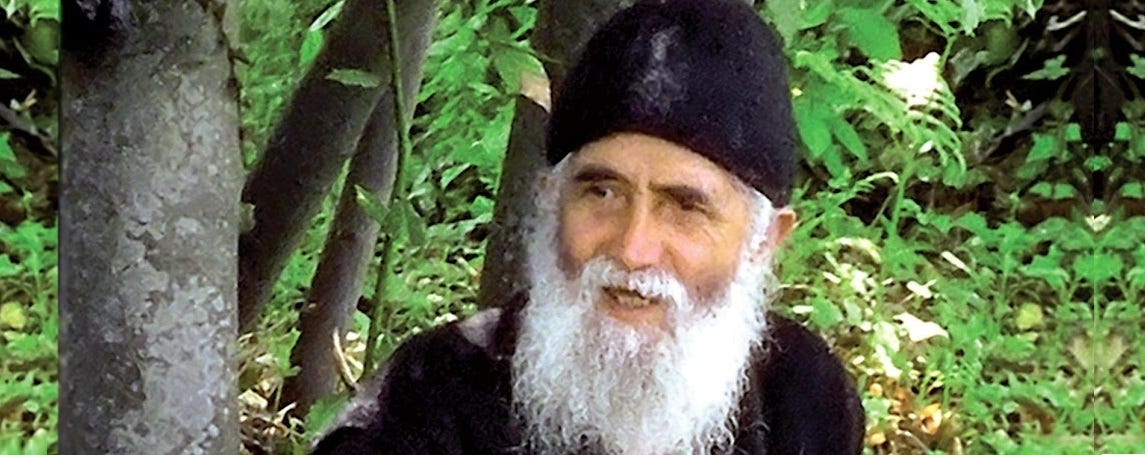

This episode was the natural outflow of the life of this Orthodox hermit, reputed for his austere, secluded lifestyle in the caves of Mt. Athos. As recounted by one of his disciples,

elder Paisios hardly ever slept. And that is not an exaggeration. I really don’t think he slept for more than one or two hours a day. He spent all of his time praying. He followed to the letter the program of daily services and prayers as practiced by all other monks living in monasteries. In addition, he kept vigil every night from sunset to sunrise, praying continuously for others and the world. I became a witness to his ceaseless prayer every time I was in his company. He prayed an hour for each different category of people, such as orphans, widows, refugees, the sick, those who were about to have an accident, soldiers at war, and others in need.

Those of us who have been shaped by what Jacques Ellul called “technique” will have a hard time relating to a vocation such as this. We have been steeped in a pragmatism where “what works” takes the place of “the highest good,” and where “every field of human activity” is reduced to the efficiency of “a machine.”4 It is counterintuitive to our mindset to acknowledge that God will actually work through such single-minded focus on mere prayer.

Having been engaged in jail visitation through my local church, I am often wont to point out that many of the inmates who experience a “prodigal’s return” to God have their “praying grandmothers” to thank. When all other facets of a self-destructive life have fallen apart, men frequently make mention of the faithfulness of a grandparent or other loved one who had prayed for them since childhood.

God approves of the vocation of prayer.

In the same way that I know this, I suspect the vocation of hermits and monastics may also be approved in God’s sight. The voluntary relinquishment of worldly comforts that is often criticized as gnostic dualism should instead be treated as an implicit affirmation of these very things.

In fasting, we give up (good) food in order to focus ourselves on a greater good.

In celibacy, we give up rights to a (blessed) family life in order to dedicate ourselves to more acute service to God

In poverty, we eliminate the trappings of (God-given) comfort that so easily distract us from commitment to God.

In all these life actions, we recognize the goodness of God’s gifts, and we voluntarily relinquish them as an offering to God. This is our “living sacrifice” (Rom. 12:1).

Conclusion

Those hermits who, from the fourth century until today, have dedicated themselves to this life of single-minded devotion are not to be dismissed as self-important spiritual solipsists. Rather, they are to be thanked for the wealth of spiritual nourishment that they have provided through their devotional literature, mystical visions, prophetic ministries, and ceaseless prayers.

The Church at large has not remained—to understate the matter—neglected by these spiritual pioneers. Indeed, even some of the most extreme hermits were of direct benefit to their local communities and followers. Simeon Stylites—the original pillar-dwelling hermit—was widely sought for his wisdom in arbitrating disputes, and Saint Anthony was a powerful exorcist to those who sought his aid. Some of the Athonite hermits of the twentieth century—such as Elders Porphyrios, Paisios, Ephraim, and Silouan—testify to the ongoing ministries offered by this vocation.5

Yes, this vocation has seen its abuses. In Augustine’s day there were a few bad apples. In Calvin’s day, it seems, there were only a few good apples (Institutes 4.8.15). But keeping in mind the principle of abusus non tollit usum, we are free to affirm those brothers and sisters who pursue this calling in good faith. I myself have found lives of these saints to be truly transformative.

Maybe you will too.

Kyriacos Markides, The Mountain of Silence: A Search for Orthodox Spirituality (New York: Doubleday, 2001), Kindle Location 618.

In addition to an array of miscellaneous patristic sources, Calvin cites the description of early monasticism primarily from Augustine’s On the Morals of the Catholic Church and On the Work of Monks.

Ford Lewis Battles, in John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion & 2, ed. John T. McNeill, trans. Ford Lewis Battles, vol. 1, The Library of Christian Classics (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 1271.

Rod Dreher, Living in Wonder: Finding Mystery and Meaning in a Secular Age (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2024), 121.

I direct readers curious about these hermits to Markides, The Mountain of Silence, as well as Elder Porphyrios, Wounded by Love: The Life and the Wisdom of Saint Porphyrios, edited by the Sisters of the Holy Convent of Chrysopigi, 2005, reprint (Limni: Denise Harvey, 2018).

“Your perfection consists in living perfectly in the place, occupation and position in which God . . . has assigned to you.” —Josemaría Escrivá

I love this quote, thank you.

This is an interesting topic, I think I would like to read A Mountain of Silence, very intriguing.

Thank you for another great article.